The PermaDesign Weblog, with Nate Downey and Melissa McDonald!

Death is the father of duty

The progenitor of permaculture, Bill Mollison, who died on September 24 at the age of 88, avoided the spiritual arena with a healthy passion. Without mercy, he would brashly challenge any and all claims as to the existence of the paranormal. “Aye, fairy worship!” he’d protest with a snort and a hyperbolic roll of his wide eyes.

Ironically, it may be time to put Mollison in prophetic terms. Okay, I know. Some of you may not be ready. He hasn’t been gone long, but please make your sobbing snappy. Time is short. Resource depletion, species extinction, climate change. Pick your pollution. Like it or not. We must quickly cultivate Mollison’s legacy. What the Hell? Why not aim high?

Like any paradigm-shifting bloke, Mollison was a profound thinker and a charismatic communicator. I’ve been blessed to see him in action several times, and in 1992 I was fortunate to have him as lead teacher of a permaculture design course at Santa Fe’s Apache Creek Ranch. I’ve had many effective teachers in my life — professionals, who blew minds on regular bases. He tops them all.

Mollison was to teaching as Jerry Garcia was to playing guitar — talented, original, exceedingly interesting and often amusing, poignant and profound. Both would go noodling off on saucy, seemingly irrelevant and half-brewed tangents. But if a patient listener gave the chow fun time enough to boil, a slippery new world would spiral into a dreamy bite of rhizomatous wisdom. Delivered with a plucky faith in life’s mercurial tempo and a preternatural ability to slow down and soften up, each master regularly provided his sagacious goods with an intense and enduring shock.

But Mollison was more than an entertaining teacher who made you giggle and grow, greater than a soulful sage who made you weep and love.

His prophetic side becomes apparent when one considers the content of his message. Like all prophesy, it’s morally significant, directly connected to the workings of the universe, and able to predict the future. Some call it mystical, religious, or transcendent. In permaculture, we use a set of self-evident ethics founded on the concept of moral responsibility, and we study predictable patterns in nature as we apply universal, science-based principles to our work.

Permaculture’s moral significance is best understood in comparison to the term “sustainability.” Both words were coined in 1972, but as synonyms go it’s critical to note that they differ almost as much as they resemble each other. Sustainability describes a condition, real or imagined, but it’s an end unto itself with no known means to attain its goal. Conversely, permaculture provides a detailed and comprehensive road map toward the sustainable Promised Land. The word itself comes complete with a built-in plan for real-world success, which is essentially this: Mimic the patterns and principles of nature whenever you affect your environment, and efficiencies will occur, yields will increase, local biodiversity levels will begin to rebound, and you will be on the road to a sustainable future.

Like sustainability, permaculture can refer to a goal, but the latter is also a moral plea, a cultural movement, a motivational philosophy, a system of design, a set of practical techniques, a wide-spectrum of authentic examples based on the same biologically based creed, and much, much more. I tend to think of permaculture as a school of thought and action — in sharp contrast to the vague and easy to co-opt term sustainability. This linguistic distinction is helpful to understand when you are trying to comprehend the internal power and universal life-forces embedded in the more-complex term.

To confirm the oracular nature of permaculture qua prophesy, let’s work our way back from 1972. In cooperation with Mollison’s student at the University of Tasmania, David Holmgren, the two ecologists developed a practical philosophy that provided the keys to human survival. As a portmanteau of permanent, agriculture, and culture, permaculture unveiled the importance of creating locally based food and energy systems in order to maintain some semblance of human civilization given our planet’s limited resources. In sharp contrast to the post-World War II soil-depleting systems of industrialized food production, permaculture was a sibylline call to action to which our culture has responded but has not yet fully embraced.

In 1978, Mollison and Holmgren published Permaculture One. After that, Holmgren mostly stayed home to create an Australian oasis. As living proof that permaculture works, he’s the movement’s well-grounded and much-loved mother figure. Tune in next time for my sainthood argument. (Well, no. Don’t—I’m in deep enough, I’d assume.)

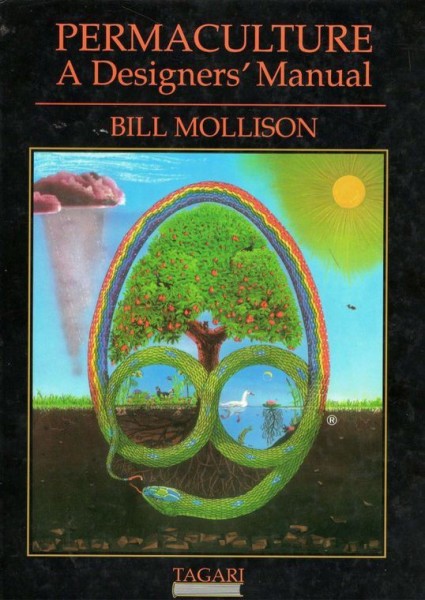

Meanwhile Mollison spent many decades exhorting the ways, means, and benefits of permaculture. By the beginning of the 1980s, he’d taught in five continents. By the end of the decade, Permaculture: A Designers’ Manual was published, and permaculture designers, permaculture teachers, and even teachers of permaculture teachers suddenly had a formidable textbook, a 580-page eco-bible to which they could refer and through which they could sound reasonably intelligent and mostly believable.

Conceived in one of the most remote corners of western civilization, the idea first swept swiftly into the fringes of alternative society. Decades later, even the New York Times, Le Monde and Aljazeera America are reporting about it. In the Guardian’s obituary on Mollison, which has close to 10,000 shares and God knows how many views, the 195-year-old international news outlet claimed that permaculture has three million practitioners and that the movement has spread to more than 140 countries.

One apostle, Robyn Francis of Djanbung Gardens, has taught 143 permaculture design courses since 1985. Last month she graduated over 40 more permaculture designers in China. The movement is growing. But what’s next?

In macabre situations like the death of a beloved guru, permies might look to the second of Mollison’s five design principles, “The problem is the solution.” Of course, the “problem” of Mollison’s mortality is a “solution” to the problem of looming cultural demise. Fortunately, given his current physical state, we don’t have a rotting-body problem. With Mollison’s death, we have a duty to disseminate a growing body of knowledge across the globe and down the street. It’s an opportunity to spread the word, so please do.

In the great tradition of ecology-based morality, which includes the work of Aldo Leopold, Masanobu Fukuoka, and Rachel Carson, Mollison recognized the dilemmas that human beings would be facing today. He found the solution and spent the rest of his life sharing it with others. May we continue his work and move it into contemporary mainstream society. And may he decay into glory and rise up through the trunks of the trees planted by those who’ve learned that we are all creators now.

11/07/2016 | (0) Comments

Comments